Popular Science: Are seagrasses capable of mycorrhiza?

For most terrestrial plants, mycorrhizal symbiosis is typical, which among other things allowed them to colonize land. It is especially important for plants in terms of getting minerals and water, which are sent to them through an extensive network of fungal hyphae. But what about seagrasses? Can they create something similar? A group of scientists around Martin Vohník from the Department of Experimental Plant Biology Faculty of Science at the Charles University tried to find out.

Detail of the root system of Mediterranean Tapeweed. Photo by M. Vohník

Detail of the root system of Mediterranean Tapeweed. Photo by M. Vohník

The catch is that seagrasses exhibit certain characteristics that reduce their chances of symbiosis with fungi: 1) they obtain nutrients through leaves, 2) many species form a lot of root hairs that are responsible for nutrient intake, 3) the roots of sea grasses are rich in aerenchyma tissue (this tissue contains a lot of air – a so-called aeration tissue) in the bark of the root, which is an area where fungal mycorrhizal structures can be most commonly found in land plants, and finally 4) seagrasses live in muddy substrates where there is little oxygen available, which restricts the development of extraradical mycelium, typical for most types of mycorrhiza. From earlier studies, it is still not clear whether seagrasses enter into a similar symbiotic relationship like their terrestrial relatives, or seemed not to do so.

Researchers examined two species of these plants – Posidonia oceanica and Cymodocea nodosa in the northwestern part of the Mediterranean Sea. The genus Posidonia is the oldest of the seagrasses group and Posidonia oceanica is endemic to the Mediterranean Sea. Its parts – rhizomes, roots and the old leaf sheaths – are very resistant to microbial degradation and thus may form layers several meters thick that are in many ways analogous to the layers of peat. Vascular plants cannot use such a pool of organically bound nutrients without the help of symbiotic bacteria or fungi.

In contrast, Cymodocea nodosa does not create such layers and typically inhabits muddy substrates at shallower depths, which is not the favorite substrate of Posidonia, and rich formation of root hairs is typical for its root system.

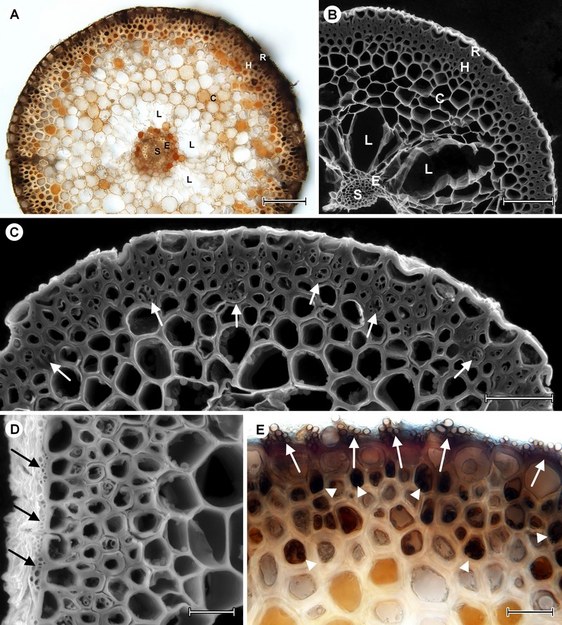

Detail of the tapeweed´s internal root structure including intracellular fungal symbionts. Photo by M. Vohník, J. Machač

Detail of the tapeweed´s internal root structure including intracellular fungal symbionts. Photo by M. Vohník, J. Machač

By examining the roots of these two species of seagrasses using light, scanning and transmission electron microscopy, it was discovered for the first time that roots of Posidonia host specific fungal symbionts. This cohabitation is anatomically and morphologically similar to that which can be found in the roots of most land plants, called DSE association (Dark Septate Endophytes), characteristic of fungal hyphae with dark septae on the surface and inside the root, dense networks of melanized hyphae on its surface and melanized microsclerotia (compact formations of condensed and thickened hyphae) inside the root cells. Despite the widespread appearance of this association (found in all surveyed locations) and its frequency in a healthy-looking population of Posidonia oceanica, it remains unclear whether the fungus is involved in receiving and transferring nutrients to the host or whether it’s useful to this dominant Mediterranean seagrass in any other way. But it’s interesting that it’s likely only one, so far undescribed, fungus, which is in great contrast with terrestrial plants, whose root systems are usually colonized by tens to hundreds of different fungal symbionts.

It’s obvious that the scope of this issue is still very broad, and sea mycorrhiza needs to remain a subject of further research.

Document Actions